As many of you know, I firmly believe that HR hiring software--AKA "applicant tracking systems"--, which far too many American enterprises offer job seekers as their only port-of-entry,

exacerbate our nation's unemployment problem and detract from companies' bottom lines (and therefore detract from the economy as a whole). So any article I come across that's critical of ATSes gets my attention.

In this article, CIO's Meridith Levinson

describes applicant tracking systems as capricious and fundamentally-flawed. She hammers home the fact that the expensive, unwieldy software American enterprises often "employ"

as their exclusive employment gatekeepers arbitrarily reject potentially great employees. As you read the article, keep in mind that

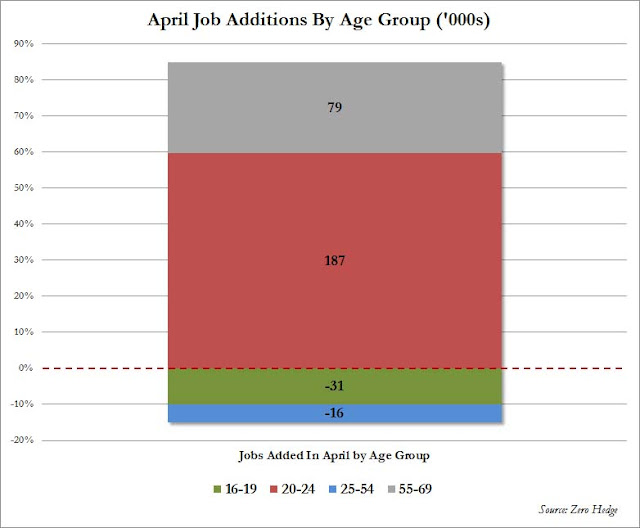

half of Americans ages 18-29 are either unemployed or underemployed. Think about how younger Americans who have less experience (and therefore have fewer keywords and numbers on their applicant profiles) and who have a smaller professional network (not that that matters much when hiring managers direct applicants to their ATSes) might be at a significant disadvantage under this hiring paradigm. This is, after all, a paradigm in which even the most talented applicants are judged by poorly-designed computer software

based on experiential criteria only. Remember, an ATS will always select someone with more degrees or experience over someone with more accomplishments. Why? Because

ATSes CAN'T IDENTIFY ACCOMPLISHMENTS.

Lou Adler, entrepreneur and best-selling author, best summarized this phenomenon in an article he

recently published on LinkedIn:

“Successful candidate will develop a new approach for reducing water usage by 50%,” is a

lot better than saying “Must have 5-10 years of environmental

engineering background including 3-5 years of wastewater management."

- See more at: http://www.ecominoes.com/2013/05/the-american-hiring-paradigm-is-broken.html#sthash.KkCw7bIz.dpuf

Lest we forget what Lou Adler, entrepreneur and best-selling author,

recently stated on LinkedIn:

“Successful candidate will develop a new approach for reducing water usage by 50%,” is a

lot better than saying “Must have 5-10 years of environmental

engineering background including 3-5 years of wastewater management."

In this case, ATSes would always choose candidates with more years of experience over those with more accomplishments that would suggest the capability of reaching the goal of reducing water usage by 50%. In fact, many ATSes require applicants to list "responsibilities". Anyone can have responsibilities. Only a select (read: overlooked) few have bona fide accomplishments.

But the people most capable of identifying accomplishments relevant to the job, hiring managers, all too often go out of their way to conceal themselves from the applicant pool. Anyway, on to the article:

Applicant tracking systems are the bane of legions of job seekers.

These systems, which employers use to manage job openings across their

enterprises and screen incoming resumes from job seekers, kill 75

percent of candidates' chances of landing an interview as soon as they

submit their resumes, according to job search services provider Preptel.

The problem with applicant tracking systems, as many job seekers know,

is that they are flawed. Very flawed. If a job seeker's resume isn't

formatted the right way and doesn't contain the right keywords and

phrases, the applicant tracking system will misread it and rank it as a

bad match with the job opening, regardless of the candidate's

qualifications.

Bersin & Associates,

an Oakland, Calif.-based research and advisory services firm

specializing in talent management, confirmed the weaknesses of applicant

tracking systems. In a test conducted last year, Bersin &

Associates created a perfect resume for an ideal candidate for a

clinical scientist position. The research firm matched the resume to the

job description and submitted the resume to an applicant tracking

system from Taleo, arguably the leading maker of these systems.

Taleo is notorious for producing ridiculously buggy software. There used to be a

great blog that described in detail the numerous functional problems with Taleo's products. Some of these problems have been fixed with recent releases. Many have not. And the fundamental flaws persist, as they do with all ATSes:

When Bersin & Associates studied how the resume rendered in the

applicant tracking system, the company saw that one of the candidate's

work experiences was lost entirely because the resume had the date typed

before the employer. The applicant tracking system also failed to read

several educational degrees the putative candidate held, which would

have given a recruiter the impression that the candidate lacked the

educational experience necessary for the job. The end result: The resume

Bersin & Associates submitted only scored a 43 percent relevance

ranking to the job because the applicant tracking system misread it.

Every American hiring manager should read that last sentence.

Josh Bersin, CEO and president of the firm, notes that since all

applicant tracking systems use the same parsing software to read

resumes, the results his company found would be typical of most systems,

not just Taleo's.

The problems with applicant tracking systems beg the question: If

they're so flawed and if they filter out good candidates, why do

employers bother to use them? The answer is simple: Bersin says they

still make recruiters' lives easier.

Stop right there. American enterprises don't use ATSes to find the best potential employees. They use them

to make recruiters' lives easier. Let's analyze that in terms of risk and reward: To reduce the workload of their recruiters, organizations

spend billions of dollars annually on buggy software that arbitrarily eliminates a significant number of talented applicants. Under that paradigm,

up to 50% of new hires "don't work out". Does the end of convenience for HR workers justify a unquestionably broken means of hiring? Levinson goes on:

Applicant tracking systems save

recruiters days' worth of time by performing the initial evaluation and

by narrowing down the candidate pool to the top 10 candidates whose

resumes the system ranks as the most relevant. Even if some good

candidates get filtered out, recruiters still have a place to start.

Better said, recruiters have a good "place to start" with the applicants who are lucky enough to win the ATS lottery and get through to a hiring manager. Those applicants may or may not be the best candidates.

PBS's "Ask the Headhunter" Nick Corcodilos

said it best:

Unemployment

is made in America by employers

who have given up control over their competitive edge -- recruiting and

hiring -- to a handful of database jockeys who are funded by HR

executives, who in turn have no idea how to recruit or hire themselves.

Seth Mason, Charleston SC

Update 01/10/15: Because I've ceased publishing ECOMINOES, I've removed a great many articles I believe have become less relevant over time. I've deleted as many links that were broken as I could find...I apologize if I missed any. Also, due to the proliferation of spam, I've closed comments and deleted the ECOMINOES Facebook page and Twitter account.

Update 01/10/15: Because I've ceased publishing ECOMINOES, I've removed a great many articles I believe have become less relevant over time. I've deleted as many links that were broken as I could find...I apologize if I missed any. Also, due to the proliferation of spam, I've closed comments and deleted the ECOMINOES Facebook page and Twitter account.