Former Reagan budget director David Stockman has been quite outspoken about the Federal Reserve's role in collapsing the economy. Much of his new book,

The Great Deformation, explains how the Fed led us into

this economic depression and how our central bank is now inflating an asset bubble that will eclipse the mid-2000s housing bubble. This

new, larger bubble, Stockman says, will eventually burst and crash the economy once more.

In The Great Deformation, Stockman frequently notes that the post-Great Recession "recovery" has been nothing but rampant Fed-fueled asset speculation. In Chapter 31, the former budget director explains that, while the speculation has been a windfall for the wealthiest among us, it's done next to nothing to improve the atrocious job market:

After the US economy liquidated excess inventory and labor

and hit its natural bottom in June 2009, it embarked upon a halting but

wholly unnatural “recovery.” The artificial prolongation of the

Bush tax cuts, the 2 percent payroll tax abatement and the spend-out of

the Obama stimulus pilfered several trillions from future taxpayers in

order to gift America’s present day “consumption units” with the

wherewithal to buy more shoes and soda pop.

But there has been no recovery of the Main Street economy where it counts; that is, no revival of breadwinner jobs and earned incomes on the free market.

What we have once again is faux prosperity. In fact, the current

Bernanke Bubble is an even sketchier version of the last one and

consists essentially of the deliberate and relentless reflation of

financial asset prices.

In practice, this amounts to a monetary version of “trickle down” economics.

By September 2012, personal consumption expenditure (PCE) was up by

$1.2 trillion from the prior peak, representing a modest 2.2 percent per

year (0.6 percent after inflation) gain from the level of late 2007.

Yet half of this gain—more than $600 billion—reflected the massive

growth of government transfer payments, and much of the rebound which

did occur in private consumption spending was concentrated in the top

10–20 percent of households. In short, the Fed’s financial repression

policies enabled Uncle Sam to fund transfer payments for the bottom

rungs of society at virtually no carry cost on the debt, while they

juiced the top rungs with a wealth effects tonic that boosted spending

at Nordstrom’s and Coach.

The Fed’s post-Lehman money printing spree has thus failed to

revive Main Street, but it has ignited yet another round of rampant

speculation in the risk asset classes. Accordingly, the net

worth of the 1 percent is temporarily back to the pre-crisis status quo

ante.

Conservatives often scoff at the phrase "1 percent". But it's absolutely true that

Fed liquidity pumping has been great for the wealthiest Americans but bad for the rest of us. The reason is simple: 1) inflation--a natural byproduct of liquidity pumping--is good for most investment classes but bad for nearly every other sector of the economy, and 2) the wealthiest among us have the majority of their net worth in investments that benefit most from inflation: equities, commodities, and real estate.

Needless to say, successful speculation in the fast money complex

is not a sign of honest economic recovery: it merely marks the prelude

to another spectacular meltdown in the canyons of Wall Street next time

the music stops.

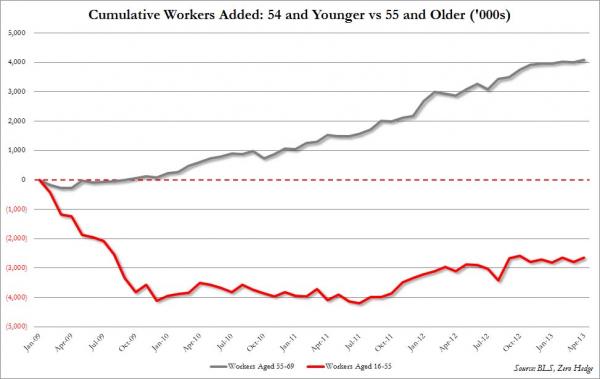

In the following subsection, Stockman details the sunset of American "breadwinner" jobs:

The precarious foundation of the Bernanke Bubble is starkly evident in the internal composition of the jobs numbers.

At the time the US economy peaked in December 2007, there were 71.8

million “breadwinner” jobs in construction, manufacturing, white-collar

professions, government, and full-time private services. These jobs

accounted for more than half of the nation’s 138 million total payroll

and on average paid about $50,000 per year—just enough to support a

family.

Breadwinner jobs also generated more than 65 percent of

earned wage and salary income and are thus the foundation of the Main

Street economy. Yet after a brutal 5.6 million loss of

breadwinner jobs during the Great Recession, a startling fact stands

out: less than 4 percent of that loss had been recovered after 40 months

of so-called recovery.

The 3 million jobs recovered since the recession ended in

June 2009, in fact, have been entirely concentrated in the two far more

marginal categories that comprise the balance of the national

payroll. More than half of the recovery (1.6 million jobs) occurred in

what is essentially the “part-time economy.” It presently includes 36.4

million jobs in retail, hotels, restaurants, shoe-shine stands, and

temporary help agencies where average annualized compensation was only

$19,000. This vast swath of the jobs economy—27 percent of the total—is

thus comprised of entry level, second earner, and episodic jobs that

enable their holders to barely scrape by.

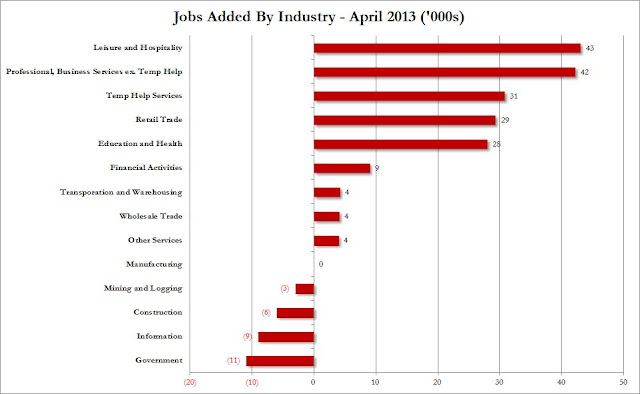

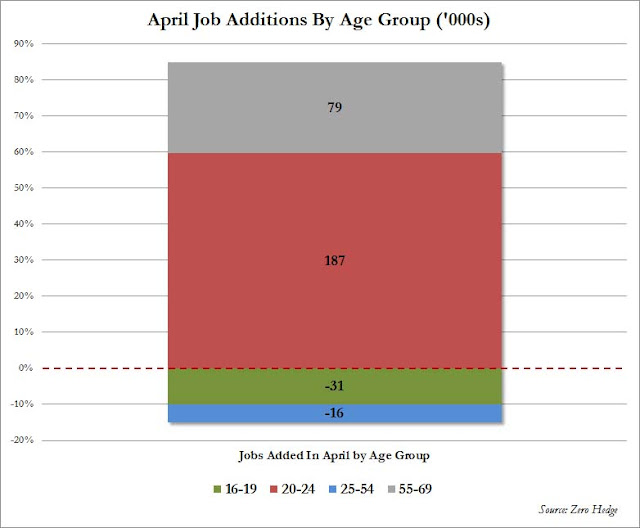

The

April jobs report exemplifies the dearth of good jobs. While April is historically the

strongest month for hiring, this April saw a woefully insufficient

number of jobs created,

more than half of the new jobs in either the hospitality industry (think: bartenders, waitresses,

etc.) or temp jobs. Again, that was in the

strongest month for hiring 5

years after Lehman.

The balance of the pick-up (1.1 million jobs) was in the HES

Complex, which consists of 30.7 million jobs in health, education, and

social services. Average compensation is slightly better at

about $35,000 annually and this category has grown steadily for years.

Its increasingly salient disability, however, is that it is almost

entirely dependent on government spending and tax subsidies, and thus

faces the headwind of the nation’s growing fiscal insolvency.

When viewed in this three category framework, the nation’s job picture reveals a lopsided aspect that thoroughly belies the headline claims of recovery.

A healthy Main Street economy self-evidently depends upon growth in

breadwinner jobs, but there has been none, even during the bubble years

before the financial crisis. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

reported 71.8 million breadwinner jobs in January 2000, yet seven years

later in December 2007—after the huge boom in housing, real estate,

household consumption, and the stock market—the number was still exactly

71.8 million.

Stockman is saying what I've been saying all along: the economy hasn't been "right" since the Fed's tech bubble burst in the early 2000s. He's saying that all we've seen in the new millennium has been cycles of artificial booms and busts built on shaky fundamentals that have never allowed a full recovery of the job market. Stockman elaborates on the shaky fundamentals in the concluding paragraphs of the subsection:

The faux prosperity of the Fed’s bubble finance is thus starkly evident.

This is the single most important metric of Main Street economic

health, and not only had there been zero new breadwinner jobs on a

peak-to-peak basis, but that alarming fact had been completely ignored

by the smugly confident monetary politburo.

Alas, the latter was blithely tracking a feedback loop of its own making.

Flooding Wall Street with easy money, it saw the stock averages soar

and pronounced itself pleased with the resulting “wealth effects.”

Turning the nation’s homes into debt-dispensing ATMs, it witnessed a

household consumption spree and marveled that the “incoming”

macroeconomic data was better than expected. That these deformations

were mistaken for prosperity and sustainable economic growth gives

witness to the everlasting folly of the monetary doctrines now in vogue

in the Eccles Building.

To be sure, nominal GDP did grow by 40 percent, or about $4

trillion, between 2000 and 2007. Yet there should be no mystery as to

how it happened. As has been noted, total debt outstanding grew

by $20 trillion during that same period. The American economy was thus

being pushed forward by a bow wave of debt, not pulled higher by rising

productivity and earned income.

Indeed, the modest gain of 7.5 million jobs during those

seven years reflected exactly this debt-driven dynamic and explains why

none of these job gains were in the breadwinner categories. Instead,

about 2.5 million were accounted for by the part-time economy jobs

described above. On an income-equivalent basis these were actually “40

percent jobs” because they represented an average of twenty-five hours

per week and paid $14 per hour, compared to a standard forty-hour work

week and a national average wage rate of $22 per hour. Thus, spending

their trillions of MEW windfalls at malls, bars, restaurants, vacation

spots, and athletic clubs, homeowners and the prosperous classes, in

effect, temporarily hired the renters and the increasing legions of

marginal workers left behind.

Likewise, another 5 million jobs were generated in the HES (health,

education, and social services) complex. Here the job count grew by 20

percent, but it was mainly due to the fact that the sector’s paymasters -

government budgets and tax-preferred employer health plans - were temporarily flush.

However, these, too, were “debt-push” jobs that paid modest wages.

While the steady 2.6 percent annual growth of HES jobs during the

second Greenspan Bubble did flatter the monthly employment “print,” it

was possible only so long as government and health plans could keep

spending at rates far higher than the growth rate of the national

economy.

Fed-fueled rampant asset speculation inflated the housing bubble, which burst and crashed the economy, making the prospect of securing a "breadwinner" job but a dream for many intelligent, educated, perfectly employable Americans. Now, the Fed is enabling what

notable economist Nouriel Roubini is calling the

"mother of all bubbles".

Seth Mason, Charleston SC

Update 01/10/15: Because I've ceased publishing ECOMINOES, I've removed a great many articles I believe have become less relevant over time. I've deleted as many links that were broken as I could find...I apologize if I missed any. Also, due to the proliferation of spam, I've closed comments and deleted the ECOMINOES Facebook page and Twitter account.

Update 01/10/15: Because I've ceased publishing ECOMINOES, I've removed a great many articles I believe have become less relevant over time. I've deleted as many links that were broken as I could find...I apologize if I missed any. Also, due to the proliferation of spam, I've closed comments and deleted the ECOMINOES Facebook page and Twitter account.